Nature and Poetry

Paolo Biscottini

The day is warm on Lake Bracciano. Autumn has just begun, but the climate is summery and the lake glitters on the different plants in Luigi Caflisch’s garden, where his studio is also located.

There is much light and I can examine the artist’s work in the best possible way. My first impression is of a sort of continuity linking the garden, the lake, the bright atmosphere and the paintings. Aside from iconographic issues, I sense how nature is reflected in the pieces, conveying the idea of mutual belonging. In the paintings, I find the same disorder as in the garden and also its light.

And why do I feel that nature’s chaos is created by the canvases? The wonder of this mutual belonging dominates and guides my visit, through Caflisch’s studio, at least at the beginning. He moves quickly. He has decided to take the paintings outside, to better show them to me. Perhaps however, he knows that these latest works truly belong to Bracciano and that the eye has to be able to glide easily from the lake to the sky to the painting.

This was not the case with his paintings of Catania, which were so obviously dark, and where the Baroque grandeur of the astonishing churches seemed to clash with the aspiration of brighter visions, while the paintbrush evoked echoes of the Roman tradition, in acrylic, at times straying into an informal gestural quality.

But it wasn’t so even in his earlier and later Roman works, where the eye became lost in the city viewed from the rooftops, in the frame of a window […] even if some still lifes, some deserted urban landscapes contain a premonition and create an indefinite discomfort. (1) The discomfort of an artist in search of a new equilibrium, of a different relationship between himself and the space. Not in the landscapes or in still lifes, but rather in living phenomenal nature, immersing himself in it, feeling a part of it.

The more recent pieces, all in oil, speak of this need, at times casting a shadow also over the myth (not new in Caflisch’s paintings), more often surrendering themselves to that sense of creative freedom, which I think can be attributed to all of Caflisch’s paintings, at least in terms of aspiration.

And these paintings of Bracciano are in fact works that arose in freedom, and express a time of leisure, of a studio far away from Rome, overlooking a lake. They speak of inner joy or perhaps of an intimate feeling where joy and suffering are joined in artistic awareness, nourished by life and hope.

Is it possible to deduce that having reached middle age, Caflisch approaches painting in a freer way, intellectually speaking? Perhaps. Certainly, life changes and above all, the artist is more distant from the academic world, and the only rules he has are those that he has given to himself, far from the models and from comparisons (the pretence of linguistic self-sufficiency (2) to which Caflisch always seems to aspire). The greatness to which he aspires today is only that of a man who seeks truth, the truth that he feels is essential in his soul. With this spirit, he dwells in nature, feeling its mysterious strength and above all its impenetrable essential nature.

He seems to welcome Klee’s invitation not to reproduce the visible but to make visible what is not always visible. In his paintings of Bracciano in fact, I see no mimetic intentions, but rather the search for atmospheres that move the image from the physical plane to the spiritual one.

Having left behind overtly religious themes, Caflisch still aspires to the sacred, perceived in the mystery that dwells in nature and in himself, where the essential nature of being lies, the invisible on which any artistic search is founded, be it words or images. In particular, it seems to me that art today has made of what is not said, of the non-form, of what is abstract in one sense, (even figuratively) the object of a slower and essentially conceptual meditation, though no less poetic and, above all, oriented towards a profound goal, which consists in the perception of mysterious areas. Luigi Caflisch’s search is all there, in this nature, a sort of studio where figures can obscure the myth, but all in all, assume mysterious value.

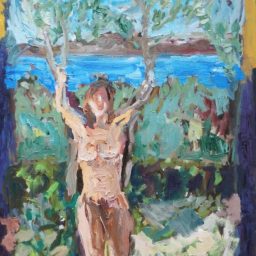

Women, mermaids, ghosts of bodily and abstract entities that seem to reveal themselves in the natural frame of a garden (where do they come from? From which hidden place do they reach this new and unexpected brightness?) for a new and sombre magnificence, to give voice to the profound mystery to which art has always aspired.

What meaning does Caflisch attribute to his sketches of female nudes (never described, never attributed to precise appearance or any erotic expression) and yet so present in his recent paintings?

The question is fundamental and should be traced back to three different characteristics in Caflisch’s art: mythology, mystery and the sacred. Different characteristics that are not distinct, but rather in proximity to one another, and that can all be traced back to the poetry of the artist. The mythology consists in a fantastic narration that leans towards an explanation of the immanent and the transcendent and has to do with mystery and thus, with what is inaccessible, where the profound meaning of being is hidden, a darkness pierced by light to which man entrusts his most authentic desire of his life.

According to Heidegger (3), the meaning of being is manifested and hidden at the same time, up until the hypothesis that being is manifested in hiding. After all, if the Psalms say, “How long, O Lord? Wilt thou forget me forever?/ How long wilt thou hide thy face from me?” (4), one can acknowledge that this form of lamentation and at the same time, invocation does not mean absence or negation but rather a special form of affirmation and manifestation of being. In this sense, the reflection becomes wider and moves to the theme of “sacred art” today. I cannot fail to mention here what I have already had the opportunity of saying several times regarding the inaccuracy of the terminology in use: art is not intrinsically sacred because it is a work of man. It can be religious in its subject matter, but not sacred. Sacred is something else, indeed it is the other, the inaccessible, the ganz Anderes, the radical alterity (5).

I recognize in all of this, the poetry of Caflisch and I trace it back to his profoundness, in which nature appears, not only in its beauty, but also in its unavoidable narrative presence. In it, is concealed the truth that the artist seeks, attributing to the female figure, not only the human dimension, but the aspiration to the sacred, as mentioned above. An artist who has dealt with religious subjects at length, and later with angelic themes seems to identify in a fleeting presence, a point of equilibrium for the composition of his paintings, the reason for a brightness that does not contradict the natural one of the lake and of the sky, but rather intensifies it, and makes it avoid the risk of a description of nature or landscapes, in order to draw it back to an inner search, not an external one of beauty and truth.

In interiore homine habitat veritas, Saint Augustine reminds us, and this is the direction in which Caflisch the painter, steers his creative energy and his search for a beauty that knows how to speak of its authentic desire to exist in being.

But Saint Augustine’s words do not tend towards dangerous self-reference. Caflisch is not an island and his relationship with external reality, be it nature, history, facts or anything else, cannot but be circular and lead back to creativity. Everything arises from within (one’s gaze, feelings, love, pain etc.), from the soul (mind, heart, desire etc.) and here it returns, establishing the uniqueness of being, its autonomy.

This is Caflisch the man, but above all, the artist and his poetry.

1. M. Bertin, Luigi Caflisch, Catania, 1996, s.p.

2. From a note in a writing by Federica Di Castro, La sera le cose sono chiare, DS, Rome, 18-30 June 1987, s.p.

3. cf. M. Heidegger, Sein und Zeit, (Being and Time) 1927; Id. Essere e Tempo, Longanesi, Milan, 1970

4. Ps 13(12):1

5. From an interview to P. Biscottini in “Presenza”

Events at Rome Art Week

2021

Free access

Vernissage Thursday 28 Oct 2021 | 16:00-20:30